Reviving pre-Geneva spirit in India ties

By N. Sathiya Moorthy

“Prime Minister (Manmohan Singh) once again

underlined the great importance we attach in India to the ability of the Tamil

people to lead a life of dignity and as equal citizens of that country,” Foreign

Secretary Ranjan Mathai told the media after the Indian leader had held two

rounds of talks with Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa on the side-lines of

Rio+20 environment summit in Brazil June 21 – a one-to-one, followed by

delegation-level talks.

Just a week afterward, on June 29, National

Security Advisor (NSA) Shivshanker Menon said thus after separate meetings with

President Rajapaksa, Economic Development Minister Basil Rajapaksa and Defence

Secretary, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, in Colombo: “India has always stood for a united

Sri Lanka within which all citizens can live in equality, justice, dignity and

self-respect. “

Between them, the two statements should help put

bilateral relations in the pre-Geneva mode -- at least as far as the ‘ethnic

issue’ part of it is concerned. Prime Minister Singh’s observation was a

reflection on the growing ground reality, where Indian concerns on the ‘Sri

Lankan issue’ were not confined to the political class in the south Indian State

of Tamil Nadu. NSA Menon reiterated, for the people and Government in the

host-nation to hear that India stood for a united Sri Lanka.

Menon’s reiteration should be contextualised to

the upcoming August 4 TESO conference being organised by former Tamil Nadu Chief

Minister and leader of the DMK partner in the ruling UPA Government of Prime

Minister Singh at Delhi. Karunanidhi’s conference would revive the call for a

‘separate Tamil State’ in Sri Lanka. That way, Menon’s call should also be a

message to the Sri Lankan Tamil community, and hard-line sections of the

Diaspora, that may have had a different construct on the Indian vote at Geneva

UNHRC earlier in the year.

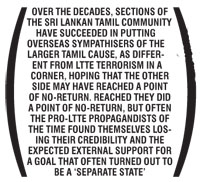

Over the decades, sections of the Sri Lankan Tamil community have succeeded in

putting overseas sympathisers of the larger Tamil cause, as different from LTTE

terrorism in a corner, hoping that the other side may have reached a point of

no-return. Reached they did a point of no-return, but often the pro-LTTE

propagandists of the time found themselves losing their credibility and the

expected external support for a goal that often turned out to be a ‘separate

State’. When clarity returned after LTTE-induced confusion, the Tamils found

that host-nations would not want to be associated not only with terrorism and

terrorists, but also a ‘separate State’ or separatist cause.

The TNA, whose leader Sampanthan, Menon met,

should read the Indian message: that India as a whole, and not just Tamil Nadu,

sympathised with the Tamil political cause. Yet, the TNA, among others in the

moderate Tamil polity in Sri Lanka, should not be under any illusion that this

was support for a separatist cause. To the extent, it is also Indian support for

the TNA’s known position of a negotiated settlement – as against the ‘Batticaloa

spirit’, which meant different things to different people, and may have been

meant to be so.

“Political reconciliation is clearly a Sri Lankan

issue, which Sri Lanka has to do,” Menon said. The onus seems to be more on the

Sri Lankan State yet he made it clear that “political reconciliation is clearly

a Sri Lankan issue which Sri Lanka has to do”. Yet, “it is a process that has

ramification for all of us”, as Menon clarified. “And it was not something that

started today or yesterday” or a few years ago, he explained further, underlying

the Indian concerns without having to spell them out.

Today, the moderate Tamil polity in Sri Lanka is

as much confused as it is confusing the rest, the Colombo Government and those

outside included. The greater moderates within the Alliance have been seeking to

stick to the middle-path, but they need support from the Government in the form

of political process. Talking to the Indian media before returning home, Menon

said that he was “not going to sit in judgment of anyone in this process”. Nor

would he set a date for Sri Lanka to complete the political process. “I don’t

think that is the way it is going to move forward,” he said.

It

is on ‘processes’ and not ‘policies’ that the reconciliation effort has been

dead-locked despite genuine interest in the Government and the TNA for reviving

the same. To each one of them, his interest and concerns are genuine, and not

that of the other. It is the kind of mistrust that has ruled ethnic relations in

Sri Lanka almost since inception, which all stake-holders, starting with the Sri

Lankan State, have wallowed in. It has become a reflexive comfort zone that they

get cocooned into when faced with reality and is called upon to address head-on.

It

is on ‘processes’ and not ‘policies’ that the reconciliation effort has been

dead-locked despite genuine interest in the Government and the TNA for reviving

the same. To each one of them, his interest and concerns are genuine, and not

that of the other. It is the kind of mistrust that has ruled ethnic relations in

Sri Lanka almost since inception, which all stake-holders, starting with the Sri

Lankan State, have wallowed in. It has become a reflexive comfort zone that they

get cocooned into when faced with reality and is called upon to address head-on.

The immediate choice is between the Government

reviving the negotiations with the TNA and the TNA entering the PSC, proposed by

the Government. Rather, it is about doing it in a way that both sides feel that

their positions are vindicated even before they flagged the issues involved. In

a way, it is ego clash. Reviving the negotiations would still be a win-win

situation that the Government in particular should acknowledge can set the right

mode and tone for the PSC process. Having stayed away after initiating the

aborted last round of talks after the TNA team had arrived at the appointed

venue, the Government has something to explain. That can be overcome, maybe, by

reviving the negotiations process, if only to lead the TNA to the PSC.

The TNA needs to acknowledge political realities,

as read by those concerned and not by it. The Alliance leadership cannot expect

to carry every partner or leader or constituency with it until they see an

‘all-acceptable’ political draft on hand. If the TNA still hopes to do so, it

would owe not to the inherent strengths of the Alliance or the leadership. It

would instead owe to the inherent weakness of such others forming part of the

Alliance. It is a reality. The Government side, it would seem, is not unaware

of the same. It is questionable however if they are abusing the TNA’s

predicament though claims are to the contrary – and that they have been

accommodative, and would remain so.

The TNA leadership has to accept that the

Government, despite the massive parliamentary majority and an even greater vote

for President Rajapaksa, both in 2010, is an uneasy coalition. President

Rajapaksa’s post-war charisma and ‘winnability’ at polls against identifiable

contenders is behind perceptions about the parliamentary majority of the

Government. Flowing from this is the argument that the Government is stalling,

and is not willing. The Government side does not seem to accept that it has a

convincing majority that it can convince at will. From self-experience, the TNA

should accept the other side’s predicament, as much as it would want the rest of

the world too to acknowledge the same in it.

Now that Provincial Council polls are on cards,

the Government has to acknowledge that the TNA’s decision to contest in the

East, and their demand for early elections in the North should be an opening for

them to move forward with the political process. The TNA had boycotted the 2008

Provincial Council polls, months after the ‘liberation’ of the East from the

clutches of the LTTE. Going by their other arguments on the ethnic front and

reconciliation process in recent months, the ground reality should not have

changed. But their mind-set has changed.

If the Government’s concern in the North is that

a possible TNA-run administration in the North could lay the foundation for

separatism, they only need to relate to the accompanying Alliance charge on

excessive military presence in the Province. Other nations, India included, have

had vast experience in handling situations. The political process can provide

the answers through permanent, constitutional solutions. The power for the

Centre to suspend elected Provincial Council administrations in the face of

threat to ‘internal security’, accompanied by constitutionally-mandated judicial

review at the first instance before further action could be initiated, needs to

be considered as a possible way out.

The TNA too has to acknowledge that that world is watching, and is watching for the first time in full bloom, the events and developments in Sri Lanka, as none of them have done it in peace time. It needs to acknowledge that the Geneva vote is neither a licence for a separatist agenda (which the TNA does not profess, however), nor is it a ticket to stalling the political process. The onus for keeping the political process alive will be as much on the TNA as on the Government – and the international community would make the delineation sooner than later.